博大精深總論前︰

Chemical reaction

A chemical reaction is a process that leads to the chemical transformation of one set of chemical substances to another.[1] Classically, chemical reactions encompass changes that only involve the positions of electrons in the forming and breaking of chemical bonds between atoms, with no change to the nuclei (no change to the elements present), and can often be described by a chemical equation. Nuclear chemistry is a sub-discipline of chemistry that involves the chemical reactions of unstable and radioactive elements where both electronic and nuclear changes can occur.

The substance (or substances) initially involved in a chemical reaction are called reactants or reagents. Chemical reactions are usually characterized by a chemical change, and they yield one or more products, which usually have properties different from the reactants. Reactions often consist of a sequence of individual sub-steps, the so-called elementary reactions, and the information on the precise course of action is part of the reaction mechanism. Chemical reactions are described with chemical equations, which symbolically present the starting materials, end products, and sometimes intermediate products and reaction conditions.

Chemical reactions happen at a characteristic reaction rate at a given temperature and chemical concentration. Typically, reaction rates increase with increasing temperature because there is more thermal energy available to reach the activation energy necessary for breaking bonds between atoms.

Reactions may proceed in the forward or reverse direction until they go to completion or reach equilibrium. Reactions that proceed in the forward direction to approach equilibrium are often described as spontaneous, requiring no input of free energy to go forward. Non-spontaneous reactions require input of free energy to go forward (examples include charging a battery by applying an external electrical power source, or photosynthesis driven by absorption of electromagnetic radiation in the form of sunlight).

Different chemical reactions are used in combinations during chemical synthesis in order to obtain a desired product. In biochemistry, a consecutive series of chemical reactions (where the product of one reaction is the reactant of the next reaction) form metabolic pathways. These reactions are often catalyzed by protein enzymes. Enzymes increase the rates of biochemical reactions, so that metabolic syntheses and decompositions impossible under ordinary conditions can occur at the temperatures and concentrations present within a cell.

The general concept of a chemical reaction has been extended to reactions between entities smaller than atoms, including nuclear reactions, radioactive decays, and reactions between elementary particles, as described by quantum field theory.

A thermite reaction using iron(III) oxide. The sparks flying outwards are globules of molten iron trailing smoke in their wake.

佛歡喜日君自安。

古來丹道欲飛仙,《咸艾》《太戊》說巫咸!

沖天火砲遊戲間,物理化學己當先?

History

Antoine Lavoisier developed the theory of combustion as a chemical reaction with oxygen.

Chemical reactions such as combustion in fire, fermentation and the reduction of ores to metals were known since antiquity. Initial theories of transformation of materials were developed by Greek philosophers, such as the Four-Element Theory of Empedocles stating that any substance is composed of the four basic elements – fire, water, air and earth. In the Middle Ages, chemical transformations were studied by Alchemists. They attempted, in particular, to convert lead into gold, for which purpose they used reactions of lead and lead-copper alloys with sulfur.[2]

The production of chemical substances that do not normally occur in nature has long been tried, such as the synthesis of sulfuric and nitric acids attributed to the controversial alchemist Jābir ibn Hayyān. The process involved heating of sulfate and nitrate minerals such as copper sulfate, alum and saltpeter. In the 17th century, Johann Rudolph Glauber produced hydrochloric acid and sodium sulfate by reacting sulfuric acid and sodium chloride. With the development of the lead chamber process in 1746 and the Leblanc process, allowing large-scale production of sulfuric acid and sodium carbonate, respectively, chemical reactions became implemented into the industry. Further optimization of sulfuric acid technology resulted in the contact process in the 1880s,[3] and the Haber process was developed in 1909–1910 for ammonia synthesis.[4]

From the 16th century, researchers including Jan Baptist van Helmont, Robert Boyle, and Isaac Newton tried to establish theories of the experimentally observed chemical transformations. The phlogiston theory was proposed in 1667 by Johann Joachim Becher. It postulated the existence of a fire-like element called “phlogiston”, which was contained within combustible bodies and released during combustion. This proved to be false in 1785 by Antoine Lavoisier who found the correct explanation of the combustion as reaction with oxygen from the air.[5]

Joseph Louis Gay-Lussac recognized in 1808 that gases always react in a certain relationship with each other. Based on this idea and the atomic theory of John Dalton, Joseph Proust had developed the law of definite proportions, which later resulted in the concepts of stoichiometry and chemical equations.[6]

Regarding the organic chemistry, it was long believed that compounds obtained from living organisms were too complex to be obtained synthetically. According to the concept of vitalism, organic matter was endowed with a “vital force” and distinguished from inorganic materials. This separation was ended however by the synthesis of urea from inorganic precursors by Friedrich Wöhler in 1828. Other chemists who brought major contributions to organic chemistry include Alexander William Williamson with his synthesis of ethers and Christopher Kelk Ingold, who, among many discoveries, established the mechanisms of substitution reactions.

倘使不知『後』與『前』?!如何平衡『變不變』!?

Equations

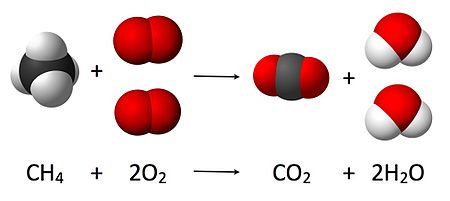

As seen from the equation CH4 + 2 O2 → CO2 + 2 H2O, a coefficient of 2 must be placed before the oxygen gas on the reactants side and before the water on the products side in order for, as per the law of conservation of mass, the quantity of each element does not change during the reaction

Chemical equations are used to graphically illustrate chemical reactions. They consist of chemical or structural formulas of the reactants on the left and those of the products on the right. They are separated by an arrow (→) which indicates the direction and type of the reaction; the arrow is read as the word “yields”.[7] The tip of the arrow points in the direction in which the reaction proceeds. A double arrow (⇌) pointing in opposite directions is used for equilibrium reactions. Equations should be balanced according to the stoichiometry, the number of atoms of each species should be the same on both sides of the equation. This is achieved by scaling the number of involved molecules (![]() and

and ![]() in a schematic example below) by the appropriate integers a, b, c and d.[8]

in a schematic example below) by the appropriate integers a, b, c and d.[8]

More elaborate reactions are represented by reaction schemes, which in addition to starting materials and products show important intermediates or transition states. Also, some relatively minor additions to the reaction can be indicated above the reaction arrow; examples of such additions are water, heat, illumination, a catalyst, etc. Similarly, some minor products can be placed below the arrow, often with a minus sign.

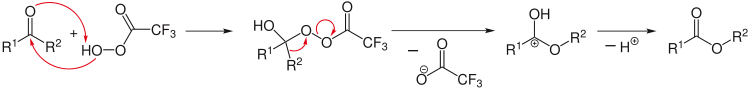

An example of organic reaction: oxidation of ketones to esters with a peroxycarboxylic acid

Retrosynthetic analysis can be applied to design a complex synthesis reaction. Here the analysis starts from the products, for example by splitting selected chemical bonds, to arrive at plausible initial reagents. A special arrow (⇒) is used in retro reactions.[9]

還請回歸大道原??!!

Elementary reactions

The elementary reaction is the smallest division into which a chemical reaction can be decomposed, it has no intermediate products.[10] Most experimentally observed reactions are built up from many elementary reactions that occur in parallel or sequentially. The actual sequence of the individual elementary reactions is known as reaction mechanism. An elementary reaction involves a few molecules, usually one or two, because of the low probability for several molecules to meet at a certain time.[11]

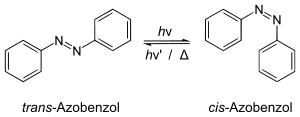

Isomerization of azobenzene, induced by light (hν) or heat (Δ)

The most important elementary reactions are unimolecular and bimolecular reactions. Only one molecule is involved in a unimolecular reaction; it is transformed by an isomerization or a dissociation into one or more other molecules. Such reactions require the addition of energy in the form of heat or light. A typical example of a unimolecular reaction is the cis–trans isomerization, in which the cis-form of a compound converts to the trans-form or vice versa.[12]

In a typical dissociation reaction, a bond in a molecule splits (ruptures) resulting in two molecular fragments. The splitting can be homolytic or heterolytic. In the first case, the bond is divided so that each product retains an electron and becomes a neutral radical. In the second case, both electrons of the chemical bond remain with one of the products, resulting in charged ions. Dissociation plays an important role in triggeringchain reactions, such as hydrogen–oxygen or polymerization reactions.

- Dissociation of a molecule AB into fragments A and B

For bimolecular reactions, two molecules collide and react with each other. Their merger is called chemical synthesis or an addition reaction.

![]()

- Another possibility is that only a portion of one molecule is transferred to the other molecule. This type of reaction occurs, for example, in redox and acid-base reactions. In redox reactions, the transferred particle is an electron, whereas in acid-base reactions it is a proton. This type of reaction is also called metathesis.

- for example

Chemical equilibrium

Most chemical reactions are reversible, that is they can and do run in both directions. The forward and reverse reactions are competing with each other and differ in reaction rates. These rates depend on the concentration and therefore change with time of the reaction: the reverse rate gradually increases and becomes equal to the rate of the forward reaction, establishing the so-called chemical equilibrium. The time to reach equilibrium depends on such parameters as temperature, pressure and the materials involved, and is determined by the minimum free energy. In equilibrium, the Gibbs free energy must be zero. The pressure dependence can be explained with the Le Chatelier’s principle. For example, an increase in pressure due to decreasing volume causes the reaction to shift to the side with the fewer moles of gas.[13]

The reaction yield stabilizes at equilibrium, but can be increased by removing the product from the reaction mixture or changed by increasing the temperature or pressure. A change in the concentrations of the reactants does not affect the equilibrium constant, but does affect the equilibrium position.

Thermodynamics

Chemical reactions are determined by the laws of thermodynamics. Reactions can proceed by themselves if they are exergonic, that is if they release energy. The associated free energy of the reaction is composed of two different thermodynamic quantities, enthalpyand entropy:[14]

![]() .

.

-

- G: free energy, H: enthalpy, T: temperature, S: entropy, Δ: difference(change between original and product)

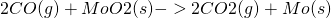

Reactions can be exothermic, where ΔH is negative and energy is released. Typical examples of exothermic reactions are precipitation and crystallization, in which ordered solids are formed from disordered gaseous or liquid phases. In contrast, in endothermicreactions, heat is consumed from the environment. This can occur by increasing the entropy of the system, often through the formation of gaseous reaction products, which have high entropy. Since the entropy increases with temperature, many endothermic reactions preferably take place at high temperatures. On the contrary, many exothermic reactions such as crystallization occur at low temperatures. Changes in temperature can sometimes reverse the sign of the enthalpy of a reaction, as for the carbon monoxide reduction ofmolybdenum dioxide:

;

;

This reaction to form carbon dioxide and molybdenum is endothermic at low temperatures, becoming less so with increasing temperature.[15] ΔH° is zero at 1855 K, and the reaction becomes exothermic above that temperature.

Changes in temperature can also reverse the direction tendency of a reaction. For example, the water gas shift reaction

is favored by low temperatures, but its reverse is favored by high temperature. The shift in reaction direction tendency occurs at 1100 K.[15]

Reactions can also be characterized by the internal energy which takes into account changes in the entropy, volume and chemical potential. The latter depends, among other things, on the activities of the involved substances.[16]

![]()

U: internal energy, S: entropy, p: pressure, μ: chemical potential, n: number of molecules, d: small change sign

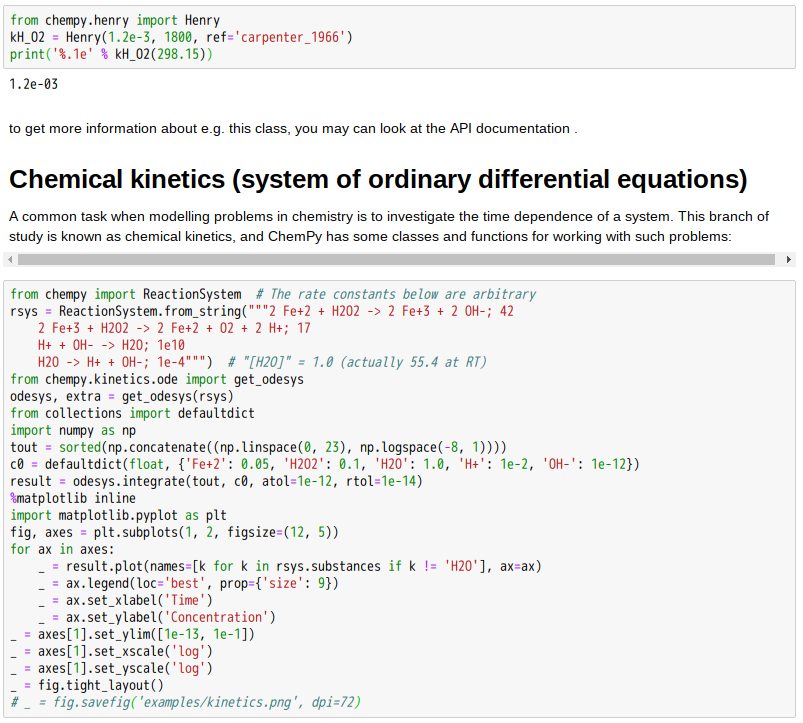

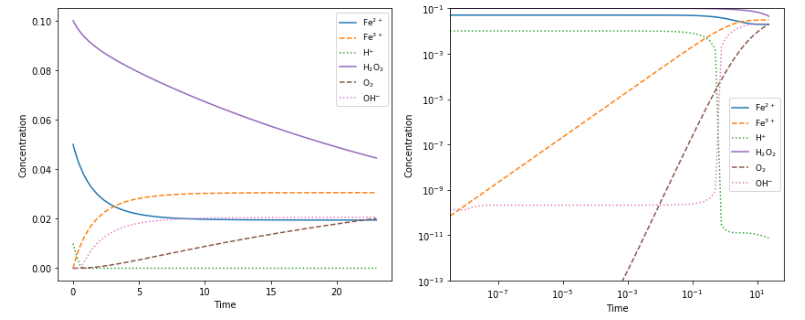

Kinetics

The speed at which reactions takes place is studied by reaction kinetics. The rate depends on various parameters, such as:

- Reactant concentrations, which usually make the reaction happen at a faster rate if raised through increased collisions per unit time. Some reactions, however, have rates that are independent of reactant concentrations. These are called zero order reactions.

- Surface area available for contact between the reactants, in particular solid ones in heterogeneous systems. Larger surface areas lead to higher reaction rates.

- Pressure – increasing the pressure decreases the volume between molecules and therefore increases the frequency of collisions between the molecules.

- Activation energy, which is defined as the amount of energy required to make the reaction start and carry on spontaneously. Higher activation energy implies that the reactants need more energy to start than a reaction with a lower activation energy.

- Temperature, which hastens reactions if raised, since higher temperature increases the energy of the molecules, creating more collisions per unit time,

- The presence or absence of a catalyst. Catalysts are substances which change the pathway (mechanism) of a reaction which in turn increases the speed of a reaction by lowering the activation energy needed for the reaction to take place. A catalyst is not destroyed or changed during a reaction, so it can be used again.

- For some reactions, the presence of electromagnetic radiation, most notably ultraviolet light, is needed to promote the breaking of bonds to start the reaction. This is particularly true for reactions involving radicals.

Several theories allow calculating the reaction rates at the molecular level. This field is referred to as reaction dynamics. The rate v of a first-order reaction, which could be disintegration of a substance A, is given by:

Its integration yields:

Here k is first-order rate constant having dimension 1/time, [A](t) is concentration at a time t and [A]0 is the initial concentration. The rate of a first-order reaction depends only on the concentration and the properties of the involved substance, and the reaction itself can be described with the characteristic half-life. More than one time constant is needed when describing reactions of higher order. The temperature dependence of the rate constant usually follows the Arrhenius equation:

where Ea is the activation energy and kB is the Boltzmann constant. One of the simplest models of reaction rate is the collision theory. More realistic models are tailored to a specific problem and include the transition state theory, the calculation of the potential energy surface, the Marcus theory and the Rice–Ramsperger–Kassel–Marcus (RRKM) theory.[17]

工具善用能畫圓??!!

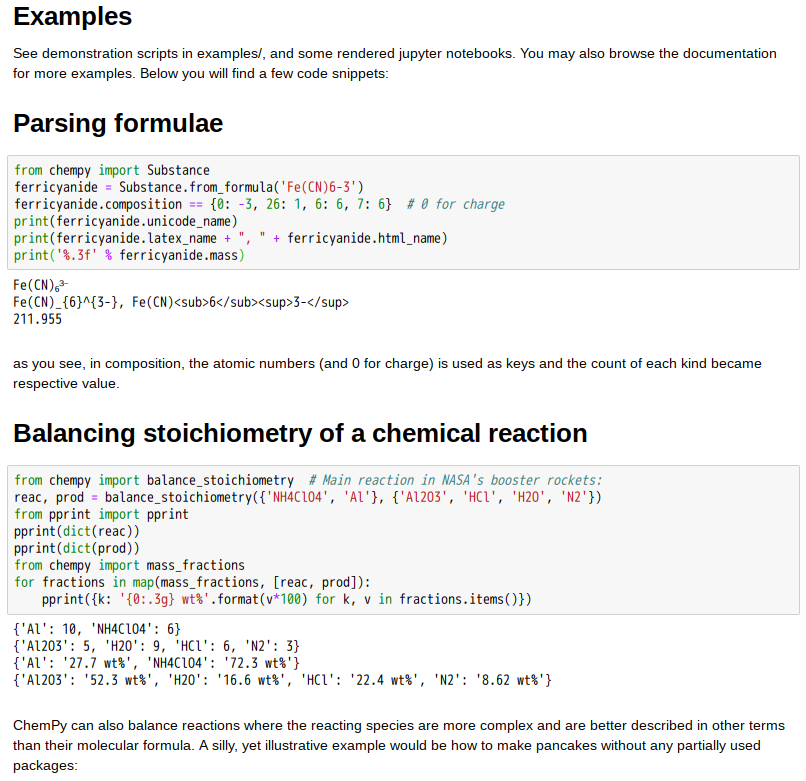

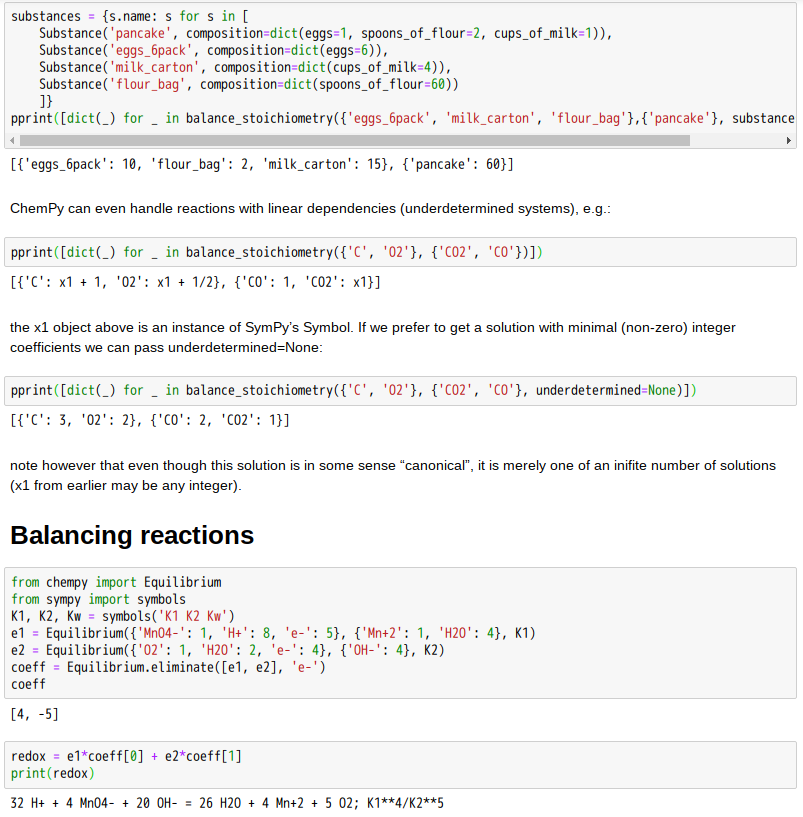

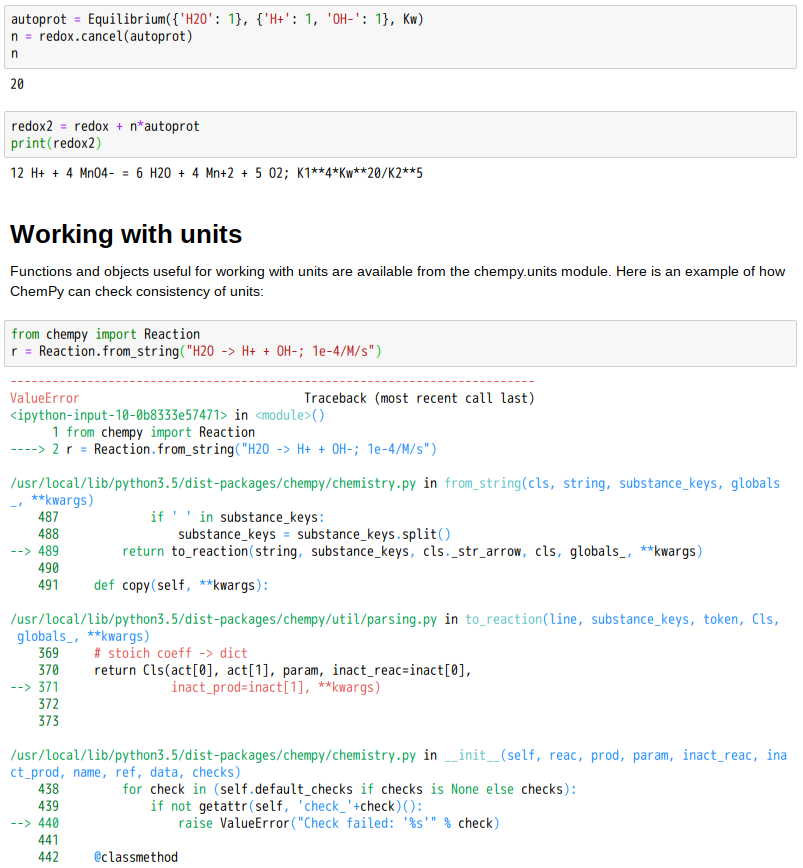

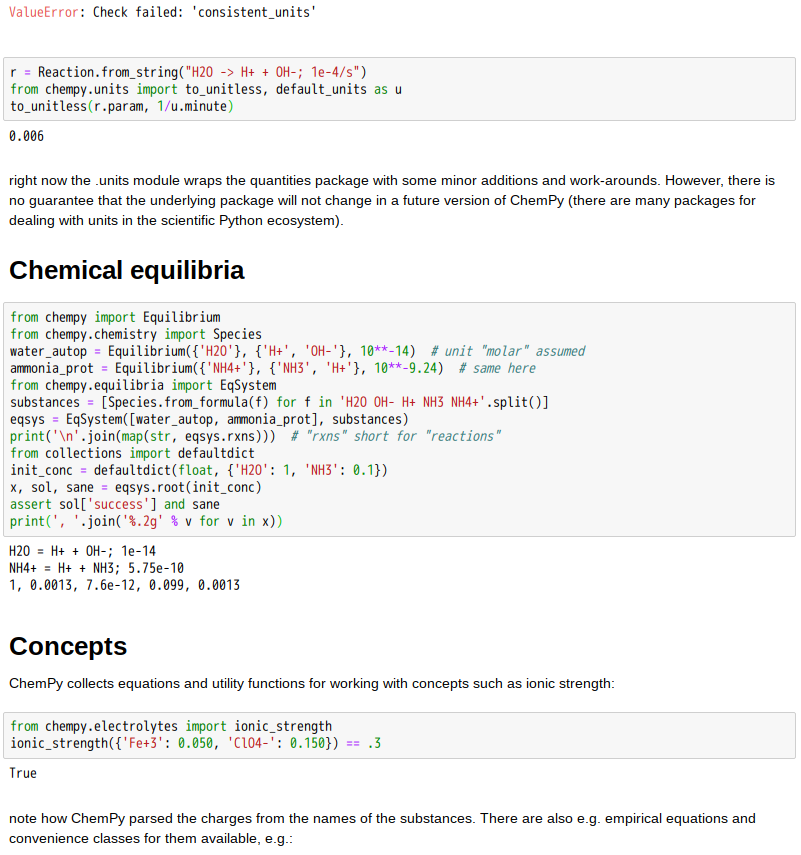

/chempy

⚗ A package useful for chemistry written in Python

ChemPy

Contents

About ChemPy

ChemPy is a Python package useful for chemistry (mainly physical/inorganic/analytical chemistry). Currently it includes:

- Numerical integration routines for chemical kinetics (ODE solver front-end)

- Integrated rate expressions (and convenience fitting routines)

- Solver for equilibria (including multiphase systems)

- Relations in physical chemistry:

- Debye-Hückel expressions

- Arrhenius & Eyring equation

- Einstein-Smoluchowski equation

- Properties (pure python implementations from the litterature)

- water density as function of temperature

- water permittivity as function of temperature and pressure

- water diffusivity as function of temperature

- water viscosity as function of temperature

- sulfuric acid density as function of temperature & weight fraction H₂SO₄

- More to come… (and contributions are most welcome!)

Documentation

The easiest way to get started is to have a look at the examples in this README, and also the jupyter notebooks. In addition there is auto-generated API documentation for the latest stable release here (and here are the API docs for the development version).

※ 註︰ 安裝

sudo apt-get install python3-pulp

sudo pip3 install chempy