如果將日常使用的個人電腦看成『計算機』 + 『輸出入界面』 + 『操作者』,那麼『自動機器』 Automata 就像無需『操作者』的獨立運行系統。既然早有『圖零測試』的議論,要是將

計算機 → 大腦

輸出入界面 → 神經網路

操作者 → ?

,『生物』能夠被當作『生化物理自動機器』嗎??大語言學家 Noam Chomsky 認為語言是人類的一種天賦,而且為人類所獨有。這從『進化論』的角度來講,『人的語言』必然得是『生物言語』的一種『突破』變化!當真人是『有靈魂』的?還是『五蘊皆空』之『人無我』與『法無我』的呢??要有人說︰他在腦海中,聽到 Tux 在『講話』!那他定然是『瘋』了的吧!!

If we knew what we were doing, it wouldn’t be called research, would it?

要是我們知道我們在幹什麼,這就不叫科學研究的了;不是嗎?

Innovation is not the product of logical thought, even though the final product is tied to a logical structure.

創新並非邏輯思維的產物,儘管最終總符合一定邏輯的結構。 ── 愛因斯坦

『色聲香味觸法』進了『腦海』怕它都是『編過碼』之『符號』,連笛卡爾都只能以『我思故我在』帶過,那『桶中之腦??』聽到無有言乎!!

在『惠施』的【泛愛萬物,天地一體也。】之論裡,作者認為︰

假使人們『體會』大自然中『陽光』與『生命』的關係, 也許能夠『感受』太陽的『久』和『大』,生起『愛.惜』萬物之心。如果人類多些『純樸』,少點『貪慾』,將更能夠認識『慎終追遠』,興起『不忍之心』。即使科學家果真找到了所謂『自私的基因』,『天下』依然會有『慈悲人』!『造物者』仍舊是將『抉擇』之『自由』交與了『生命』的吧!!

既然人類能學會『萬邦言語』,那該會有『基本 ○ □ 』的吧!大千世界中的『情意相通』生命現象也許訴說同一件事而已,『創造』以及『賦予』符號『意義』乙事,祇是『自然而然』的哩!!怎就不能有『解讀者』的存在呢??

那些『死掉的文字』與『滅絕的語言』並非是為著『來者解謎』而存在,若問『謎題』大概將是怎『興替不斷』的啊!只不過不管『歷史』曾經多少『邦國』,隨著『地域』和『時代』講過哪些『語音』的言語,也許還是必須有『解讀者』的吧!!

怎可『 ㄒㄗ 』 = 『 ㄒㄧㄢˊ ㄗㄜˊ 』這樣論斷呢?更不要說那還是『被翻譯』過的『企鵝語』哩!又誰知 Tux 會如何『笑』的了? ?

─── 《TUX@RPI ︰ 《咸澤碼訊》》

曾經有『自勝者強』之時,恐不以『勝人者有力』為尚,如

今果不合時宜乎??

聞道或有先後,術業也可專攻,此古今之法則也。所以『鬼谷子』一書可以通達遊戲『設計者』之心思,往來縱橫無礙︰

鬼谷子被喻為縱橫家之鼻祖的原因是其下有蘇秦與張儀兩個叱吒戰國時代的傑出弟子〔見《戰國策》〕。另有孫臏與龐涓亦為其弟子之說[3][4]。

《鬼谷子》

捭闔第一

粵若稽古聖人之在天地間也,為眾生之先,觀陰陽之開闔以名命物 ;知存亡之門戶,籌策萬類之終始,達人心之理,見變化之朕焉,而守司其門戶。故聖人之在天下也,自古至今,其道一也。變化無窮,各有所歸,或陰或陽,或柔或剛,或開或閉 ,或弛或張。是故聖人一守司其門戶,審察其所先後,度權量能,校其伎巧 短長。

夫賢、不肖;智、愚;勇、怯;仁、義;有差。乃可捭,乃可闔,乃可進,乃可退,乃可賤,乃可貴;無為以牧之。審定有無,與其實虛,隨其嗜欲以見其志意。微排其所言而捭反之,以求其實,貴得其指。闔而捭之,以求其利。或開而示之,或闔而閉之。開而示之者,同其情也。闔而閉之者,異其誠也。可與不可,審明其計謀 ,以原其同異。離合有守,先從其志。

即欲捭之,貴周;即欲闔之,貴密。周密之貴微,而與道相追。捭之者,料其情也。闔之者,結其誠也,皆見其權衡輕重,乃為之度數,聖人因而為之慮。其不中權衡度數,聖人因而自為之慮。故捭者,或捭而出之,或捭而內之。闔者,或闔而取之,或闔而去之。

捭闔者,天地之道。捭闔者,以變動陰陽,四時開閉,以化萬物;縱橫反出,反覆反忤,必由此矣。捭闔者,道之大化,說之變也。必豫審其變化。吉凶大命繫焉。口者,心之門戶也。心者,神之主也。志意、喜欲、思慮、智謀,此皆由門戶出入。故關之矣捭闔,制之以出入。捭之者,開也,言也,陽也。闔之者,閉 也,默也,陰也。陰陽其和,終始其義。故言「長生」、「安樂」、「富貴」 、「尊榮」、「顯名」、「愛好」、「財利」、「得意」、「喜欲 」,為「陽」,曰 「始」。故言「死亡」、「憂患」、「貧賤」、「苦辱」、「棄損」、「亡利」、「失意」、「有害」、「刑戮」 、「誅罰」,為「陰」,曰「終」。諸言法陽之類者,皆曰「始」 ;言善以始其事。諸言法陰之類者,皆曰「終」;言惡以終其謀。

捭闔之道,以陰陽試之。故與陽言者,依崇高。與陰言者,依卑小 。以下求小,以高求大。由此言之,無所不出,無所不入,無所不可。可以說人,可以說家,可以說國,可以說天下。為小無內,為大無外;益損、去就、倍反,皆以陰陽御其事。陽動而行,陰止而藏;陽動而出,陰隱而入;陽還終陰,陰極反陽。以陽動者,德相生也。以陰靜者,形相成也。以陽求陰,苞以德也;以陰結陽,施以力也。陰陽相求,由捭闔也。此天地陰陽之道,而說人之法也。為萬事之先,是謂圓方之門戶。

反應第二

古之大化者,乃與無形俱生。反以觀往,覆以驗來;反以知古 ,覆以知今;反以知彼,覆以知此。動靜虛實之理不合於今,反古而求之。事有反而得覆者,聖人之意也,不可不察。

人言者,動也;己默者,靜也。因其言,聽其辭。言有不合者,反而求之,其應必出。言有象,事有比;其有象比,以觀其次。象者 ,象其事;比者,比其辭也。以無形求有聲。其釣語合事,得人實也。其猶張罝而取獸也。多張其會而同之,道合其事,彼自出之,此釣人之網也。常持其網而驅之。其不言無比,乃為之變。以象動之,以報其心、見其情,隨而牧之。己反往,彼覆來,言有象比,因而定基。重之、襲之、反之、覆之,萬事不失其辭。聖人所誘愚智,事皆不疑。

故善反聽者,乃變鬼神以得其情。其變當也,而牧之審也。牧之不審,得情不明。得情不明,定基不審。變象比必有反辭以還聽之。欲聞其聲,反默;欲張, 反斂;欲高,反下;欲取,反與。欲開情者,象而比之,以牧其辭。同聲相呼,實理同歸。或因此,或因彼 ;或以事上,或以牧下。此聽真偽,知同異,得其情詐也。動作言默,與此出入;喜怒由此以見其式;皆以先定為之法則。以反求覆 ,觀其所託,故用此者。己欲平靜以聽其辭,察其事、論萬物、別雌雄。雖非其事,見微知類。若探人而居其內,量其能,射其意也 。符應不失,如螣蛇之所指,若羿之引矢。

故知之始己,自知而後知人也。其相知也,若比目之魚;其見形也 ,若光之與影也。其察言也不失,若磁石之取鍼;如舌之取蟠骨。其與人也微,其見人也疾;如陰與陽,如陽與陰,如圓與方,如方與圓。未見形,圓以道之;既見形,方以事之。進退左右,以是司之。己不先定,牧人不正,事用不巧,是謂忘情失道。 己審先定以牧人,策而無形容,莫見其門,是謂天神。

───

也可以究觀遊戲『使用者』的想法,出入心想事成。然而天下事卻常有『所思』之不周,『所想』又不備之時,終究如之奈何耶?!

─── 摘自《W!O+ 的《小伶鼬工坊演義》︰【新春】 復古派 《九》神機鬼藏》

況且還存在『機心巧詐』之說,此

所以先言機械效益也!!

Mechanical advantage

Mechanical advantage is a measure of the force amplification achieved by using a tool, mechanical device or machine system. The device preserves the input power and simply trades off forces against movement to obtain a desired amplification in the output force. The model for this is the law of the lever. Machine components designed to manage forces and movement in this way are called mechanisms.[1] An ideal mechanism transmits power without adding to or subtracting from it. This means the ideal mechanism does not include a power source, is frictionless, and is constructed from rigid bodies that do not deflect or wear. The performance of a real system relative to this ideal is expressed in terms of efficiency factors that take into account departures from the ideal.

The law of the lever

The lever is a movable bar that pivots on a fulcrum attached to or positioned on or across a fixed point. The lever operates by applying forces at different distances from the fulcrum, or pivot. The location of the fulcrum determines a lever’s class. Where a lever rotates, continuously, it functions as a rotary 2nd-class lever. The motion of the lever’s end-point describes a fixed orbit, where mechanical energy can be exchanged. (see a hand-crank as an example.)

In modern times, this kind of rotary leverage is widely used; see a (rotary) 2nd-class lever; see gears, pulleys or friction drive, used in a mechanical power transmission scheme. It is common for mechanical advantage to be manipulated in a ‘collapsed’ form, via the use of more than one gear (a gearset). In such a gearset, gears having smaller radii and less inherent mechanical advantage are used. In order to make use of non-collapsed mechanical advantage, it is necessary to use a ‘true length’ rotary lever. See, also, the incorporation of mechanical advantage into the design of certain types of electric motors; one design is an ‘outrunner’.

As the lever pivots on the fulcrum, points farther from this pivot move faster than points closer to the pivot. The power into and out of the lever is the same, so must come out the same when calculations are being done. Power is the product of force and velocity, so forces applied to points farther from the pivot must be less than when applied to points closer in.[1]

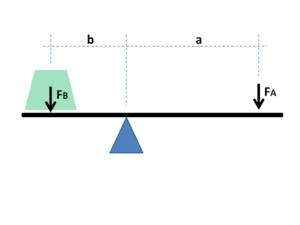

If a and b are distances from the fulcrum to points A and B and if force FA applied to A is the input force and FB exerted at B is the output, the ratio of the velocities of points A and B is given by a/b, so the ratio of the output force to the input force, or mechanical advantage, is given by

This is the law of the lever, which was proven by Archimedes using geometric reasoning.[2] It shows that if the distance a from the fulcrum to where the input force is applied (point A) is greater than the distance bfrom fulcrum to where the output force is applied (point B), then the lever amplifies the input force. If the distance from the fulcrum to the input force is less than from the fulcrum to the output force, then the lever reduces the input force. Recognizing the profound implications and practicalities of the law of the lever, Archimedes has been famously attributed the quotation “Give me a place to stand and with a lever I will move the whole world.”[3]

The use of velocity in the static analysis of a lever is an application of the principle of virtual work.

Speed ratio

The requirement for power input to an ideal mechanism to equal power output provides a simple way to compute mechanical advantage from the input-output speed ratio of the system.

The power input to a gear train with a torque TA applied to the drive pulley which rotates at an angular velocity of ωA is P=TAωA.

Because the power flow is constant, the torque TB and angular velocity ωB of the output gear must satisfy the relation

which yields

This shows that for an ideal mechanism the input-output speed ratio equals the mechanical advantage of the system. This applies to all mechanical systems ranging from robots to linkages.

Gear trains

Gear teeth are designed so that the number of teeth on a gear is proportional to the radius of its pitch circle, and so that the pitch circles of meshing gears roll on each other without slipping. The speed ratio for a pair of meshing gears can be computed from ratio of the radii of the pitch circles and the ratio of the number of teeth on each gear, its gear ratio.

Two meshing gears transmit rotational motion.

The velocity v of the point of contact on the pitch circles is the same on both gears, and is given by

where input gear A has radius rA and meshes with output gear B of radius rB, therefore,

where NA is the number of teeth on the input gear and NB is the number of teeth on the output gear.

The mechanical advantage of a pair of meshing gears for which the input gear has NA teeth and the output gear has NB teeth is given by

This shows that if the output gear GB has more teeth than the input gear GA, then the gear train amplifies the input torque. And, if the output gear has fewer teeth than the input gear, then the gear train reduces the input torque.

If the output gear of a gear train rotates more slowly than the input gear, then the gear train is called a speed reducer (Force multiplier). In this case, because the output gear must have more teeth than the input gear, the speed reducer will amplify the input torque.

其實是『時』來『時』去,『應時』而已矣◎