老子第四十二章中講︰道生一,一生二,二生三,三生萬物。是說天地生萬物就像四季循環的自然而然,如果『人』或將成為『亦大』,就得知道大自然 『益』生之道,能循本溯源貴能『得一』。他固善於『觀水』,盛讚『上善若水』,卻也深知水為山堵之『蹇』、人為慾阻之『蒙』難,故於第三十九章中又講︰

昔之得一者,天得一以清,地得一以寧,神得一以靈,谷得一以盈,萬物得一以生,侯王得一以為天下貞。其致之。天無以清則恐裂,地無以寧則恐發,神無以靈則恐歇,谷無以盈則恐竭,萬物無以生則恐滅,侯王無以貞高則恐蹶。故貴以賤為本,高以下為基。是以侯王自謂孤寡不穀,此非以賤為本耶?非乎?人之所惡,唯孤寡不穀,而侯王以為稱。故致譽無譽。不欲琭琭如玉,珞珞如石。

,希望人們知道所謂『道德』之名,實在說的是『得到』── 得道── 的啊!!如果乾坤都『沒路』可走,人又該往向『何方』??

昔時吳越之爭,越王勾踐『臥薪嘗膽』逐夢復國,此事紀載於《史記‧越王勾踐世家》,在此我們將談及一人亦載之於史記︰

范蠡‧史記‧貨殖列傳

昔者越王句踐困於會稽之上,乃用范蠡、計然。計然曰:『知斗則修備,時用則知物,二者形則萬貨之情可得而觀已。故歲在金,穰;水,毀;木,饑;火,旱。旱則資舟,水則資車,物之理也。六歲穰,六歲旱,十二歲一大饑。夫糶,二十病農,九十病末。末病則財不出,農病則草不辟矣。上不過八十,下不減三十,則農末 俱利,平糶齊物,關市不乏,治國之道也。積著之理,務完物,無息幣。以物相貿易,腐敗而食之貨勿留,無敢居貴。論其有餘不足,則知貴賤。貴上極則反賤,賤下極則反貴。貴出如糞土,賤取如珠玉。財幣欲其行如流水。』修之十年,國富,厚賂戰士,士赴矢石,如渴得飲,遂報彊吳,觀兵中國,稱號『五霸』。

范蠡既雪會稽之恥,乃喟然而嘆曰:「計然之策七,越用其五而得意。既已施於國,吾欲用之家。」乃乘扁舟浮於江湖,變名易姓,適齊為鴟夷子皮,之陶為朱公。 朱公以為陶天下之中,諸侯四通,貨物所交易也。乃治產積居。與時逐而不責於人。故善治生者,能擇人而任時。十九年之中三致千金,再分散與貧交疏昆弟。此所謂富好行其德者也。後年衰老而聽子孫,子孫修業而息之,遂至巨萬。故言富者皆稱陶朱公。

文子治國富民之策有七,越王只用其五就洋洋得意。范蠡細省已用『天時』、『地利』二者,所餘不用,不就是『人和』不用了嗎?勾踐得國後必將失人,此時不乘扁舟浮於江湖,怕我連命都不保了。陶朱公之為後世所稱的『財神』,不因他能得之於天下成大富巨萬,而因他能『三聚三散』用之於天下。此時如果再讀讀莊子的二則寓言︰

莊子‧胠篋之竊鉤者誅,竊國者為諸侯;

聖人不死,大盜不止。雖重聖人而治天下,則是重利盜跖也。為之斗斛以量之,則並與斗斛而竊之;為之權衡以稱之,則並與權衡而竊之;為之符璽以信之,則並與符璽而竊之;為之仁義以矯之,則並與仁義而竊之。何以知其然邪?彼竊鉤者誅,竊國者為諸侯,諸侯之門而仁義存焉,則是非竊仁義聖知邪?故逐於大盜,揭諸侯,竊仁義並斗斛權衡符璽之利者,雖有軒冕之賞弗能勸,斧鉞之威弗能禁。此重利盜跖而使不禁者,是乃聖人之過也。

莊子‧秋水之無用用大;

惠子謂莊子曰:魏王貽我大瓠之種,我樹之成而實五石。以盛水漿,其堅不能自舉也;剖之以為瓢,則瓠落無所容。非不呺然大也,吾為其無用而掊之。

莊子曰:夫子固拙于用大矣!宋人有善為不龜手之藥者,世世以洴澼絖為事。客聞之,請買其方百金。聚族而謀曰:『我世世為洴澼絖,不過數金,今一朝而鬻技百金,請與之。』客得之,以說吳王。越有難,吳王使之將。冬,與越人水 戰,大敗越人,裂地而封之。能不龜手一也;或以封,或不免於洴澼絖,則所用之異也。今子有五石之瓠,何不慮以為大樽,而浮於江湖,而憂其瓠落無所容?則夫子猶有蓬之心也夫!

─── 《跟隨□?築夢!!》

一個『玩具』

竹蜻蜓

竹蜻蜓是一種古老的兒童玩具,由軸和槳翼組成,多以竹木製做 。嚴格來說,竹蜻蜓應包括槳翼,轉軸和套在轉軸外的竹筒三個主要部份 ,雖然光是槳翼加轉軸也能玩, 但是只能充當作直升機玩。只有三個零件組成一體才能當自轉旋翼機玩。 中國晉朝葛洪所著的《抱朴子》是紀錄類似竹蜻蜓最早的動力機械《抱朴子》 :「若能乘蹻者,可以周流天下,不拘山河。凡乘蹻道有三法:一曰龍蹻、二曰虎蹻、三曰鹿盧蹻。或服符精思,若欲行千里,則以一時思之。若晝夜十二時思之,則可以一日一夕行萬二千里 ,亦不能過此,過此當更思之,如前法。或用棗心木為飛車 ,以牛革結環劍以引其機,或存念作五蛇六龍三牛交罡而乘之,上升四十里,名為太清。《抱朴子》一書也有這樣的記述:「或用栆心木為飛車,以牛革街環劍,以引起幾。或存念作五蛇六龍三牛 、交罡而乘之,上升四十里,名為太清。太清之中,其氣甚罡,能勝人也。」

Modern Japanese taketombo bamboo-copters; wooden type with winding thread (left); plastic type (right)

A decorated Japanese taketombopropeller

能『有何用』?卻足以啟發 George Cayley ,令李約瑟大感驚訝︰

Bamboo-copter

The bamboo-copter, also known as the bamboo dragonfly or Chinese top (Chinese zhuqingting (竹蜻蜓), Japanese taketombo 竹蜻蛉), is a toy helicopter rotor that flies up when its shaft is rapidly spun. This helicopter-like top originated in Warring States period China around 400 BC, and was the object of early experiments by English engineer George Cayley, the inventor of modern aeronautics.[1]

In China, the earliest known flying toys consisted of feathers at the end of a stick, which was rapidly spun between the hands and released into flight. “While the Chinese top was no more than a toy, it is perhaps the first tangible device of what we may understand as a helicopter.”[1]

The Jin dynasty Daoist philosopher Ge Hong‘s (c. 317) book Baopuzi (抱樸子 “Master Who Embraces Simplicity”) mentioned a flying vehicle in what Joseph Needham calls “truly an astonishing passage”.[2]

Some have made flying cars [feiche 飛車] with wood from the inner part of the jujube tree, using ox-leather (straps) fastened to returning blades so as to set the machine in motion [huan jian yi yin chiji 環劍以引其機]. Others have had the idea of making five snakes, six dragons and three oxen, to meet the “hard wind” [gangfeng 罡風] and ride on it, not stopping until they have risen to a height of forty li. That region is called [Taiqing 太清] (the purest of empty space). There the [qi] is extremely hard, so much so that it can overcome (the strength of) human beings. As the Teacher says: “The kite (bird) flies higher and higher spirally, and then only needs to stretch its two wings, beating the air no more, in order to go forward by itself. This is because it starts gliding (lit. riding) on the ‘hard wind’ [gangqi 罡炁]. Take dragons, for example; when they first rise they go up using the clouds as steps, and after they have attained a height of forty li then they rush forward effortlessly (lit. automatically) (gliding).” This account comes from the adepts [xianren 仙人], and is handed down to ordinary people, but they are not likely to understand it.[2]

Needham concludes that Ge Hong was describing helicopter tops because “‘returning (or revolving) blades’ can hardly mean anything else, especially in close association with a belt or strap”; and suggests that “snakes”, “dragons”, and “oxen” refer to shapes of man-lifting kites.[3] Other scholars interpret this Baopuzi passage mythologically instead of literally, based on its context’s mentioning fantastic flights through chengqiao (乘蹻 “riding on tiptoe/stilts”) and xian (仙 “immortal; adept”) techniques. For instance, “If you can ride the arches of your feet, you will be able to wander anywhere in the world without hindrance from mountains or rivers … Whoever takes the correct amulet and gives serious thought to the process may travel a thousand miles by concentrating his thoughts for one double hour.”[4] Compare this translation.

Some build a flying vehicle from the pith of the jujube tree and have it drawn by a sword with a thong of buffalo hide at the end of its grip. Others let their thoughts dwell on the preparation of a joint rectangle from five serpents, six dragons, and three buffaloes, and mount in this for forty miles to the region known as Paradise.[4]

This Chinese helicopter toy was introduced into Europe and “made its earliest appearances in Renaissance European paintings and in the drawings of Leonardo da Vinci.”[5] The toy helicopter appears in a c. 1460 French picture of the Madonna and Child at the Musée de l’Ancien Évêché in Le Mans, and in a 16th-century stained glass panel at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London.[6][7] A c. 1560 picture by Pieter Breughel the Elder at the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna depicts a helicopter top with three airscrews.[2]

“The helicopter top in China led to nothing but amusement and pleasure, but fourteen hundred years later it was to be one of the key elements in the birth of modern aeronautics in the West.”[8] Early Western scientists developed flying machines based upon the original Chinese model. The Russian polymath Mikhail Lomonosov developed a spring-driven coaxial rotor in 1743, and the French naturalist Christian de Launoy created a bow drill device with contra-rotating feather propellers.[1]

In 1792, George Cayley began experimenting with helicopter tops, which he later called “rotary wafts” or “elevating fliers”. His landmark (1809) article “On Aerial Navigation” pictured and described a flying model with two propellers (constructed from corks and feathers) powered by a whalebone bow drill.[9] “In 1835 Cayley remarked that while the original toy would rise no more than about 6 or 7.5 metres, his improved models would ‘mount upward of 90 ft (27 metres) into the air’. This then was the direct ancestor of the helicopter rotor and the aircraft propeller.”[10]

Discussing the history of Chinese inventiveness, the British scientist, sinologist, and historian Joseph Needham wrote, “Some inventions seem to have arisen merely from a whimsical curiosity, such as the ‘hot air balloons’ made from eggshells which did not lead to any aeronautical use or aerodynamic discoveries, or the zoetrope which did not lead onto the kinematograph, or the helicopter top which did not lead to the helicopter.”[11]

直升機

直升機是一種由一個或多個水平旋轉的旋翼提供向上升力和推進力而進行飛行的航空器。直升機具有大多數固定翼航空器所不具備的垂直升降、懸停、小速度向前或向後飛行的特點。這些特點使得直升機在很多場合大顯身手。直升機與固定翼飛機相比,其缺點是速度低、耗油量較高、航程較短。

飛行原理

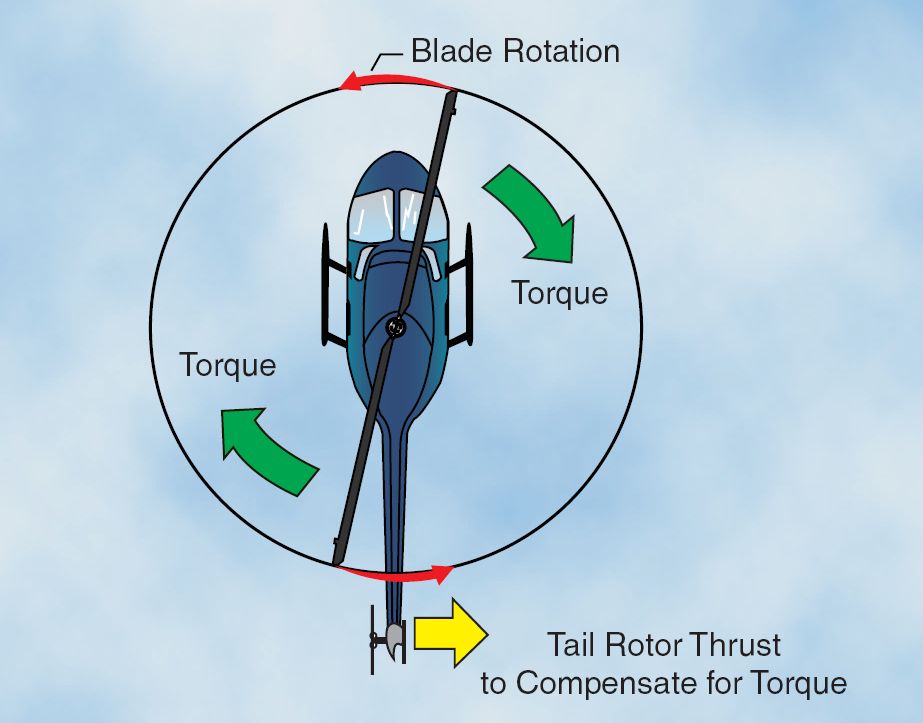

直升機的升力產生原理與固定翼飛機的機翼相似,機翼與空氣之間發生相對運動,進而產生升力。只不過這個升力是來自於繞固定軸旋轉的「旋翼」。旋翼不像固定翼飛機那樣依靠整個機體向前飛行來使機翼與空氣產生相對運動,而是依靠自身旋轉產生與空氣的相對運動。但是,在旋翼提供升力的同時,直升機機身也會因反扭矩(與驅動旋翼旋轉等量但方向相反的扭矩,即反作用扭矩)的作用而具有向反方向旋轉的趨勢。對於單旋翼直升機,為了平衡反扭矩,常見的做法是以另一個小型旋翼,即尾槳,在機身尾部產生抵消反向運動的力矩。對於多旋翼直升機,多採用旋翼之間反向旋轉的方法來抵消反扭矩的作用,因此在附圖的運作說明中可以見得,由上俯視一個順時針旋轉的主翼,它的尾槳會是向黃色箭頭所指方向推力的。]

直升機和旋翼機的外觀和性能相似,但旋翼機比較簡單和低價,但不如直升機的多方面的特殊性能,而是介乎於普通的固定翼飛機和直升機中間,所以用途較狹而專業化的航空機構通常擁有直升機但鮮有採用旋翼機。

直升機旋翼運作說明

貫通『理論』及『實務』得一者,憑借『想象之羽翼』凌空,果不能『築夢踏實』耶☆

多旋翼直升機

四軸飛行器有四個旋翼來懸停、維持姿態及平飛。它的四個旋翼大小相同,分布位置接近對稱。